Operation Anvil

.... A visit to the French RivieraExcerpt from Joe Hagen's book "Memories of World War II"

We did not know where the next invasion would take place but this time it was for a good reason. President Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill could not agree. Churchill wanted us to invade the Balkans probably because he was thinking ahead to peace and the division of Europe into areas of influence by the Allies. Stalin wanted a southern France invasion for the same reason as Churchill but with the opposite objective. Roosevelt was the deciding vote for southern France primarily because it would be less costly in American lives. France, who really did not have a vote, was anxious to send their Free French and Foreign Legion into action on their own soil. Finally the decision was made to land in the French Riviera. The name of the operation was changed from Anvil to Dragoon and D-day was set for August 15, 1944. Churchill was responsible for the name change claiming that he was dragooned into accepting the plan.

Everything was ship shape aboard and we were ready for action except for one notable exception. We did not have a small boat officer, Our previous officers and boat crews had been detached at Normandy. Since then we received five replacement LCVPs and boat crews but not even one officer for them. Among ourselves we wondered if one of us would be volunteered. By now my E for engineering rating had been changed to DE meaning that I was

now deemed eligible for Deck Officer duties so I was in the pool. The most Likely candidate was Lt. Carter our gunnery officer. He was the most athletic of us and indicated he would not object to the assignment. However, just before the operation, we welcomed aboard Lt. Campbell. He also was very athletic and gung ho.We carried troops of the 36th Division. This was the division with the large red T patch denoting that it was, at least originally, comprised of soldiers from Texas. This was a veteran group having fought in Africa, Sicily and Italy. The CO of this contingent, a silver leaf colonel, shared my stateroom with me and I learned something about their past experiences. He said on the previous invasions they had paid their dues and thought some other division should be making the first wave assault in this one. They had since landing in Africa had a 300 percent troop replacement. Many casualties had been hospitalized and then returned to the Division without any R & R. They thought the French troops should make the initial assault but were told the 36th were needed because they were experienced. This was not the first or the last time I heard of this type of logic.

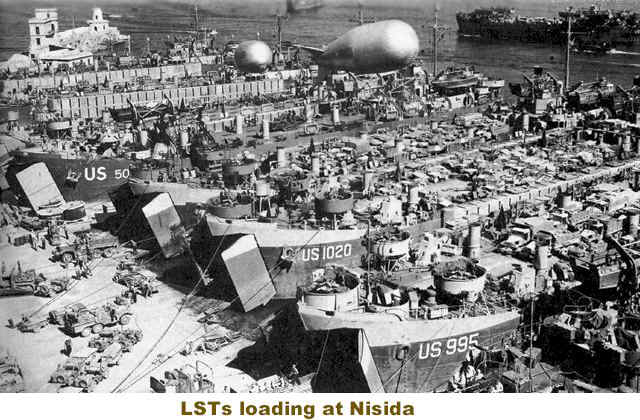

I had forgotten that Nisada was the place where we took on the troops for the invasion but recently I came across this following picture showing the LST 50 on the beach loading. This is from Morison's History. I was not sure that this was our ship and thought that it could be a five hundred number with the last digit hidden by the ship in front of it. However, like our ship the number was smaller than the letters, U.S. The other ships have letters and numbers of the same size.

Some of the LSTs had davits for carrying only two LCVPs while we had six davits the same as the ship in the picture. I do not recall that we employed barrage balloons in Operation Anvil. It is probably that the barrage balloons, shown in the photograph, were being towed by ships along side of us. When all of the equipment and troops were loaded, we headed back to Calvi.

Our tank deck was loaded with large trucks and half tracks. Our main deck carried jeeps and other small vehicles carrying anti-aircraft weapons. They were of relative small caliber of a size larger than 50 calibre but smaller than our 40mm. I think they were 27mm and were effective only against planes that flew low enough to make strafing runs. The troops did not do much joking around but seemed engrossed in having their weapons in top order. Once when I returned to my stateroom I found the Colonel had just finished cleaning his 45 and was busy sharpening his combat knife. I remarked that the targeted beach was steep and the men would not have to wade very far like the troops did at Normandy. He replied that he hated to have his men go into action with wet feet and was sure the boat crews could be persuaded to hit the beach hard.

Just before we were to depart for the invasion, our Captain was called for a meeting on the Group Commander's ship. He went there in one of our LCVPs with the ship's company crew and gave them orders to wait for him for a return run to our ship. After meeting the Captain of another LST invited our Captain to visit his ship. They went in the other LST's boat leaving ours standing by. In a short time we were ordered to get under way and our Captain rushed back to our ship and completely forgot that his boat was still standing by. When he finally realized it there was not time to retrieve our boat and we left minus one LCVP and crew.

We were part of the Camel force consisting of about one hundred ships including 14 LSTs. The USS Bayfield was the amphibious control ship under the command of Rear Admiral Lewis who had replaced the late Admiral Moon. Our assigned landing was at Green Beach close to the resort town of St. Tropez. H hour again was about 6:00 a.m. and our infantry troops climbed down cargo nets into four LCVPs. Lt. Campbell and the Colonel were in the lead boat. We could see them make the landing and it appeared to be unopposed. We were instructed with the other LSTs to sail around in a circle. The water was deep and the operation controller did not want any of us to anchor. The beach accommodated two LSTs at a time and the Beachmaster would call us in depending on the urgency of our cargo. While circling our boats came back and only one reported receiving fire. It was from a machine gun on a small island. A sergeant on board observed where the shells were landing and said it was nothing ot worry about. He fired his Garand from a prone position on the stern and the machine gun went silent.

All of our boats returned with damaged propellers. The Colonel had been serious about not wanting to fight with wet feet! We had spare propellers on board and in less than a half hour we had raised the boats in the davits, replaced the bent props and had them back in the water.

Three pairs of LSTs were called to beach while we were waiting. After several hours the Beachmaster called for LST 282 and then LST 50 to beach. At the time of the call, our position in the circle was nearest the beach and we broke from the circle and headed to the beach. The LST 282 was on the far side of the circle and although it was called before us, it ended up following us towards the beach. While going to the beach a single enemy plane, a JU 88, appeared at a very high altitude. A fire ball appeared by the plane and then a plane-like object started falling to the ground. I thought that one plane had been shot down by another one but then realized that the falling object was a rocket propelled, radio controlled bomb. We started firing at both objects without success. The bomb was traveling too fast and the plane was well beyond the range even of our 40mm Bofors. The soldiers on the main deck started firing their anti-aircraft guns without waiting for firing orders but this was a futile gesture. What we needed was the fire power of five inch guns like those on the destroyers but they were further out to sea. We watched the bomb change direction and finally zero in on the LST 282. It hit the main deck at midships, blasting through the tank deck, the engine room and the bottom hull. The 282 went forward another 100 yards and sank in shallow water with the main deck above the water line.

The LST 282 was a few hundred yards from us and we continued to the beach but the LCVP with Lt. Campbell aboard went to the rescue. Many of the soldiers had jumped overboard and with only a belt buoyancy device were having a hard time of it. Lt. Campbell lowered the ramp on the LCVP and with his crew pulled many of the soldiers out of the water. He then jumped in and being a strong swimmer was able to pull other soldiers to the boat. Then an unfortunate thing happened. The rescued soldiers instead of moving back from the ramp stayed there and their combined weight was enough to force the bow under water and the LCVP sunk. A real heroic effort turne out to be fruitless.We still had not been able to replace our elevator motor and although the temporary repair had worked fine, I thought we would be able to salvage the motor from the LST 282 and with a couple of machinists took a boat to the 282 and boarded it. I started walking to the elevator and stepped over a charred mass only to realize it was the torso of a human body. I was momentarily gripped with revulsion and thought that I would throw up but I continued to the elevator anyway. There I found that their elevator motor

had been broken and repaired the same as ours. There had been forty casualties aboard. The skipper was credited with action that prevented this number from being higher and was awarded the Navy Cross.The unloading went without incident. We were told that after a brief skirmish the Germans retreated as fast as they could. The beach was to be protected by two large gun emplacements. The concrete was finished but guns were not available and they had installed wooden dummies to confuse Allied Intelligence. When the time came to retract from the beach we found out we were stuck. Normally by running our screws in reverse, the water action would wash the sand from beneath our ship and free it. In this case the beach was not sand but cobble stones. Our stern anchor was of no help because it was deep and therefore the wrong angle for pulling us astern. An army engineer with a tremendous bulldozer came and pushed against our bow doors but our ship would not budge. Finally a sea going tug came to our rescue and we were able to retract and anchor off-shore and wait for sailing orders.

Then an incident occurred that still bothers me. A small boat pulled along side that had a German soldier sprawled on the deck. The coxs'n had taken a badly wounded soldier on board with instructions to take him some place for treatment. He had not found anyone that would treat him and by the time he reached our boat the coxs'n said he thought he was dead. None of our medics went down to the boat to check him out but one of our seaman called to the coxs'n and asked if there were any souvenirs on him. This incident still haunts me. The German soldier was just a young kid -not much different than the young men in our crew. I wish I had taken the initiative to have him examined and treated if he was still alive.

Several hours later we received our sailing orders with Ajacio, Corsica as our destination. The German Naval threat in the Mediterranean was now nil and we sailed without an escort. When we reached Ajacio we found the boat crew, that was left behind before the operation, waiting for us. They had found out that we were not coming back to Calvi and that our next port of call would be Ajacio. Without orders from anyone, they had put to sea. With just a magnetic ship's compass they had navigated almost the full west coast of Corsica. At that time they did not know how rough the Mediterranean sea can become. On reaching port they went to the Naval base and received dormitory berths and mess privileges. They then had the bright idea of asking for rations at the Army base. This was OK'D and with the surplus food they were able to trade with the civilians for things like wine, fruit and other goodies. They were doing alright but their boat did not fare as well. They left it tied up to a pier and a British ship, in attempting to dock smashed into it and sunk it. It had already been raised and was being repaired when we arrived but we had to leave without it. We were scheduled for a second run to France and this time it was supposed to be Marseille.

Marseille.....A port too far!

Since the battle front had moved well inland very soon after D-day, beach landings were not required. We were assigned for our second run into France to take French troops from Africa to the port of Marseille. I can not recall the name of the place where we loaded the troops but believe it was in Algeria. I vaguely recall taking on a French pilot and when asked how we would fit in our designated berth motioned with his elbows that he would squeeze into what ever space was available.

Most of the t troops taken on board were Free French Forces. We also had some from the French Foreign Legion and some black Senegalese colonial troops. The French were very enthusiastic about returning to their homeland and brought on board two of the largest casks of wine that I had ever seen. They must have had an early start on the wine since while they were driving their vehicles to position them on our main deck they were running into the ventilation stacks and any other object that got in their way. The Senegalese were fierce looking warriors with scarred faces but the French officers treated them harshly. One of the Senegalese soldiers was nervous about climbing down a cargo net into a boat and a French officer kicked him in the face for hesitating.

The Senior French Officer of the group came on board and asked if any of our officers spoke French. None of us did. He then asked if any of us spoke German. I admitted that I had been exposed to high school German. They had several German speaking Foreign Legionaries in their detachment and I attempted to communicate with one of them. I failed miserably and as a result the tri-lingual French Officer decided to make the trip with us. He was a very charming person and we enjoyed his company. In our wardroom, he entertained us with stories and card tricks. One of the most intriguing card tricks, I remember to this day.

We were lucky in the assignment of the troops to our ship; we had absolutely no problems with them. On the other hand, one of our group was assigned troops of Berbers. They had very little mechanized equipment but there were two to three times as many persons than an LST is equipped to handle. For every eight soldiers there was one woman assigned to do their cooking and what ever else they needed. The Captain of the LST protested that they did not have a galley or sanitary facilities to take care of such a large number of people. The reply came back that neither was required.

We anticipated that this would be the most pleasant of all of our runs. Just a couple of hundred miles across the calm Mediterranean sea without any danger of encountering any German Naval activity. At our destination we would be able to enjoy the wonderful city of Marseille. We thought there would be a celebration with the French troops arriving on their own soil and that we would be in the middle of the festivities. I was about to learn a geography lesson! Marseille is located at the mouth of the Rhone River. The valley formed by the river is unobstructed by mountains and this clear path runs completely across France from the English Channel. The wind that sweeps down this path has a name, Mistral. In the book, Lust for Life, Irving Stone, described the wind as having a maddening effect on Van Gogh during his stay at Arles. It did not drive us mad but it ruined all plans.

Within a hundred miles of Marseille the sea became increasingly rough. The wind velocity increased and we were in the roughest storm I ever encountered. We were in a convoy of about ten LSTs with orders to stay in formation and on course with a heading directly to Marseille. Now an LST does not have a rigid frame like a destroyer nor can it cut through the seas like one. With its shallow draft and wide beam, an LST will roll and survive some very rough seas. It can not take the pitching experienced by heading directly into a storm. We could see the deck plates ripple with each wave front.

One of our LCVPs broke loose from its davit and crashed on to the deck and was held precariously by the forward line. We looked to see how the other LSTs were doing and found that one of them had lost its bow doors. The ramp is what makes the ship water tight and the LST did not appear to be any danger

of sinking. We secured all the water tight doors and were constantly inspecting the hull for any damage. After many hours of this pounding we detected cracks in the main deck plates originating at a hatch approximately at mid ships. The cracks were transverse and in the direction towards the sides of our ship.

The Captain gave me the responsibility of evaluating the danger of these cracks.He also reported this problem to the Group Commandeer whose response was to "stay the course". My first report was that the cracks were minor and did not threaten the safety of the ship. However, hour by hour the cracks grew and finally reached one side of our ship. While I watched, a crack developed in the side plates and started downward. I deemed that if this continued, our ship could break in half and so advised our Captain. The Group Commander then released us from the convoy and ordered us to head south and return to Algeria. While we had been under way for two days fighting the storm, we had made such little head way that it took us less than a day to return to port.

As we unloaded, I had a strong feeling of disappointment. It was the only time we failed to accomplish a mission!

Copyright 2002, Joe Hagen, all rights reserved

Landingship.com © 2005-2026 Site by Dropbears